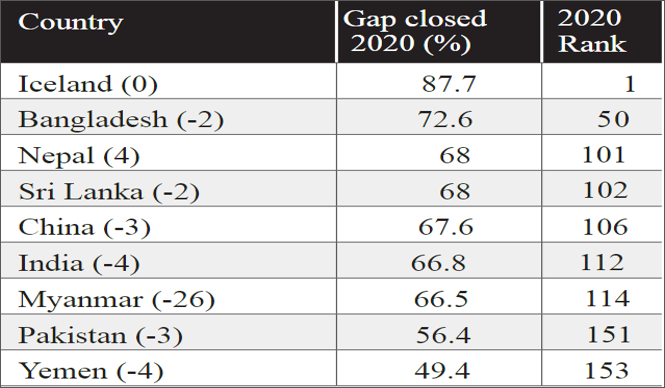

Global Gender Gap Index

- Released by World Economic Forum’s.

- It measures

○Economic participation and opportunity,

○Educational attainment,

○Health and survival, and

○Political empowerment.

- India dropped four places, from 2018, to take the 112th rank in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index 2019-2020.

- In the health and survival parameter, India’s performance is dismal, ranking 150th out of 153 countries.

- Global Rankings

- Iceland topped the gender parity rankings, redressing 87.7% of the gender gap. India was ranked 112th, having addressed only 66.8% of the gap.

- Iceland topped the gender parity rankings, redressing 87.7% of the gender gap. India was ranked 112th, having addressed only 66.8% of the gap.

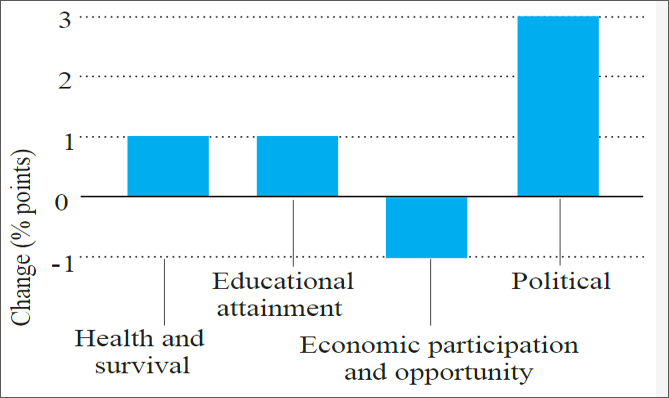

Economic woes

- Barring the economic participation index, all sub-indices witnessed marginal improvement, globally, compared to 2018.

Unhealthy rank

- Among all indices, India’s rank was the worst in the Health and Survival parameter which is computed in terms of life expectancy for women and sex ratio at birth.

- India ranked second-worst among South Asian and BRICS nations in the sex ratio category.

- For all sub-indices, the highest possible score is 1 (gender parity) and the lowest possible score is 0 (imparity).

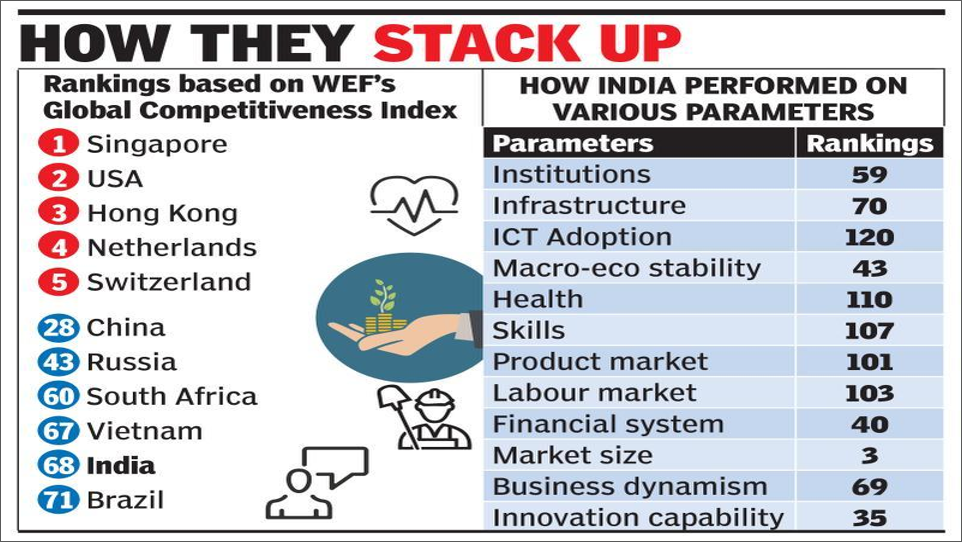

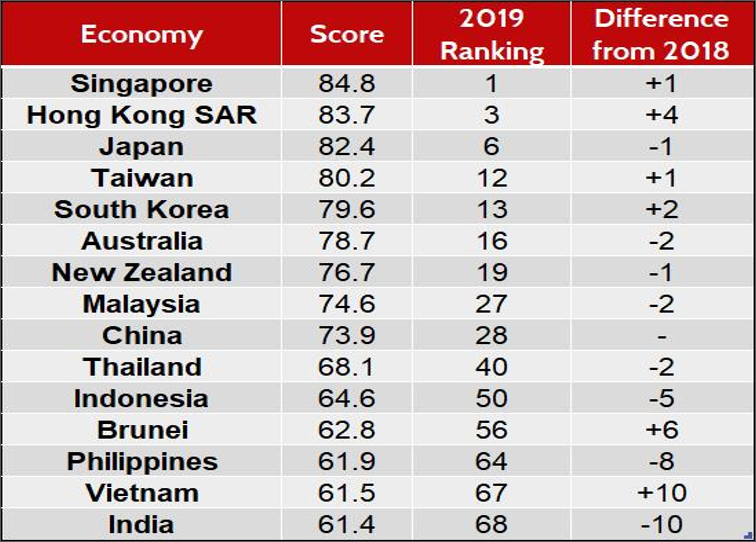

Global Competitiveness Index

- First launched in 1979.

- Compiled annually by Geneva-based World Economic Forum (WEF).

- India at 68th position among 141 countries – that’s 10 ranks below its 2018 position in the same index.

What is GCI?

- This is the fourth version of the global competitiveness index – hence referred to as GCI 4.0 – and it was introduced in 2018.

- The 141 countries mapped by this year’s GCI account for 99 per cent of the world’s GDP.

- The basic notion behind the GCI is to map the factors that determine the Total Factor Productivity (TFP) in a country.

- The TFP is essentially the efficiency with which different factors of production such as land, labour and capital are put to use to create the final product.

- It is believed that it is the TFP in an economy that determines the long-term economic growth of a country.

- The GCI 4.0 tracks data and/or responses on 12 factors divided into 4 broad categories.

- The first category is the “Enabling Environment” and this includes factors such as the state of infrastructure, institutions, the macroeconomic stability of the country and its ability to adopt new technology.The second category is “Human Capital” and includes health and level of skills in the economy.

- The third is the state of “Markets” such as those for labour, product, financial and the overall market size.

- The last category is “Innovation Ecosystem” which includes business dynamism and innovation capability.

- For example, the average GCI score across the 141 economies that were studied this year was 60.7. This means that the ‘distance to the frontier’ stands at almost 40 points.

How did India fare?

- India’s 2019 overall score (61.4) fell by merely 0.7 when compared to its 2018 score.

- But this slippage was enough for it to slide down 10 ranks in the list.

- The report states: “In South Asia, India, in 68th position, loses ground in the rankings despite a relatively stable score, mostly due to faster improvements of several countries previously ranked lower”.

- Some of the countries that were close to India and made rapid progress were Colombia (which had a score of 62.7, up 1.1 points from last year, and now ranked 57th), Azerbaijan (62.7, +2.7, 58th), South Africa (62.4, +1.7, 60th) and Turkey (62.1, +0.5, 61st).

- India trails China (28th, 73.9) by 40 places and 14 points.

- But within South Asia , it is the best performer and is followed by Sri Lanka (the most improved country in the region at 84th), Bangladesh (105th), Nepal (108th) and Pakistan (110th).

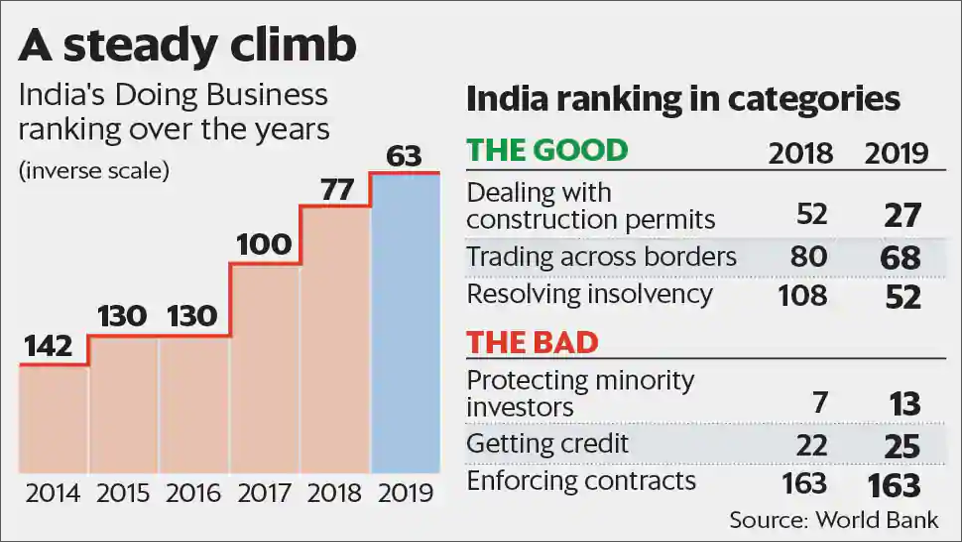

Ease of Doing Business 2020 report

- Released by World Bank

- India has moved 14 places to be 63rd among 190 nations in the World Bank’s ease of doing business ranking.

- The country was 77th among 190 countries in the previous ranking last year, an improvement by 23 places.

- Sustained business reforms over the past several years has helped India jump 14 places to move to 63rd position in this year’s global ease of Doing Business rankings.

- While there has been substantial progress, India still lags in areas such as enforcing contracts (163rd) and registering property (154th).

- It takes 58 days and costs on average 7.8% of a property’s value to register it, longer and at greater cost than among OECD high-income economies.

- And it takes 1,445 days for a company to resolve a commercial dispute through a local first-instance court, almost three times the average time in OECD high-income economies.

- The latest reforms are in the Doing Business areas of Starting a Business, Dealing with Construction Permits, Trading Across Borders and Resolving Insolvency.

- In Doing Business 2020, India along with other top improvers implemented a total of 59 regulatory reforms in 2018/19—accounting for one-fifth of all the reforms recorded worldwide.

- Doing Business acknowledges the 10 economies that improved the most on the ease of doing business after implementing regulatory reforms.

- In Doing Business 2020, the 10 top improvers are Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Togo, Bahrain, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, China, India, and Nigeria.

- Completing the procedures required to build a warehouse now costs only 4% of the warehouse value.

- Building quality control measures were also improved, and now only six economies in the world score better than India’s 14.5 out of 15 on this index.

- Importing and exporting became easier for companies for the fourth consecutive year.

- With the latest reforms, India now ranks 68th globally on this indicator and performs significantly better than the regional average.

- Doing business ranking is based on quantitative indicators on regulation for starting a business, dealing with

○construction permits,

○getting electricity,

○registering property,

○getting credit,

○protecting minority investors,

○paying taxes,

○trading across borders,

○enforcing contracts and resolving insolvency.

World Development Report 2020

- Released by World Bank

- Report titled “World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains”.

- In an era of slowing trade and growth, developing countries can achieve better outcomes for its people through reforms to boost their participation in global value chains.

- Global value chains have played an important part in the growth, by enabling firms in developing countries to make significant gains in productivity, and by helping them transition from commodity exports to basic manufacturing.

- To ensure sustained social support for trade, policymakers need to ensure that the benefits of global value chains are widely shared among a broad range of groups — especially the poor and women — and that the environment is protected.

Global trade

- According to the report, creation of the European single market — together with the integration of China, India, and the Soviet Union into the global economy —

○created a huge new product and labour markets, and

○so firms could sell the same goods to more people and

○take advantage of economies of scale,

○leading to the further deepening of GVCs.

Impact on poverty

- Since gains in growth from global value chains are larger than from trade in final products, their impact on poverty reduction is also larger.

- Regions in Mexico and Vietnam that participated more intensively in global value chains experienced greater reductions in poverty.

- Further, firms in global value chains draw people into more productive manufacturing and services activities and tend to employ more women, supporting structural transformation in developing countries, it said.

- The report highlights the steps countries can take to attract GVC investments, even if they have been largely left out of the value chain revolution.

- Small steps — such as speeding up customs and reducing border delays — can yield big benefits for countries making the transition from commodity exports to basic manufacturing.

What are Global Value Chain, GVCs?

- Companies used to make things primarily in one country.

- That has all changed.

- Today, a single finished product often results from manufacturing and assembly in multiple countries, with each step in the process adding value to the end product.

- Through GVCs, countries trade more than products; they trade know-how, and make things together. Imports of goods and services matter as much as exports to successful GVCs.

- GVCs integrate the know-how of lead firms and suppliers of key components along stages of production and in multiple offshore locations.

- The international, inter-firm flow of know-how is the key distinguishing feature of GVCs.

- How countries engage with GVCs determines how much they benefit from them.

Why are GVCs important for growth?

- GVCs are a powerful driver of productivity growth, job creation, and increased living standards.

- Countries that embrace them grow faster, import skills and technology, and boost employment.

- With GVC-driven development, countries generate growth by moving to higher-value-added tasks and by embedding more technology and know-how in all their agriculture, manufacturing, and services production. GVCs provide countries the opportunity to leap-frog their development process.

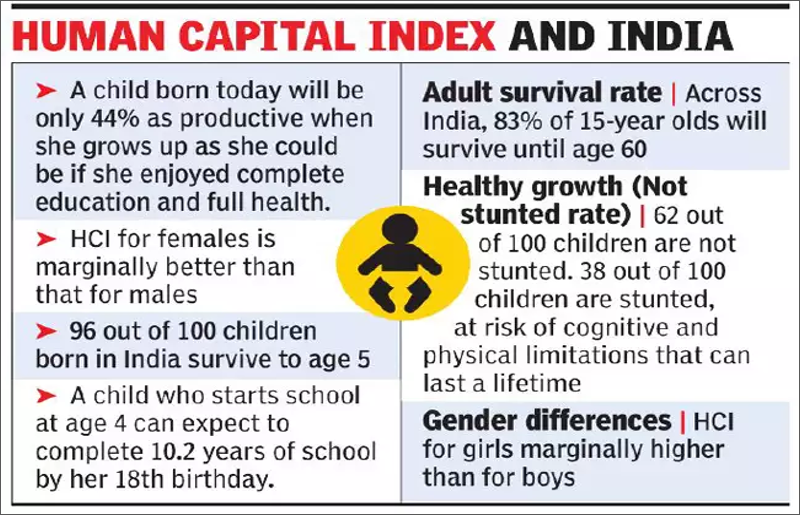

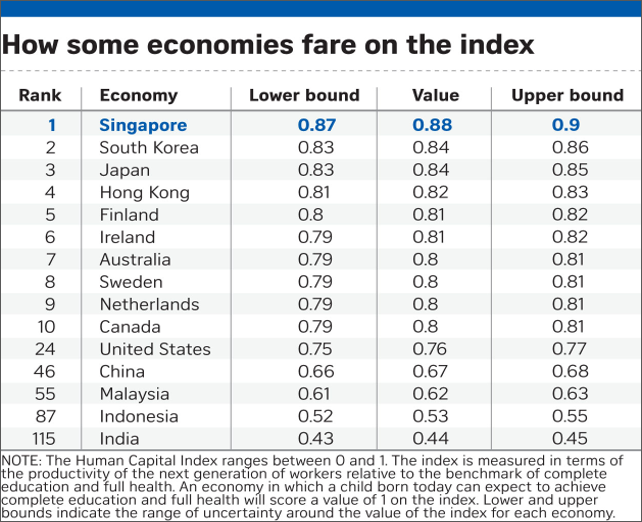

Human Capital Index (HCI)

- Eirst HCI, Compiled by the World Bank as part of the World Development Report 2019.

- India is ranked at 115 position in the index with its score of 0.44 on a scale of 0 to 1 coming even below the average score for South Asia.

- HCI, which covered 157 countries, seeks to measure the amount of human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by age 18.

- The index values convey the productivity of the next generation of workers, compared to a benchmark of complete standard education and full health.

- It has three components – survival, expected years of quality-adjusted school, and health environment.

- For 56% of the world’s population HCI score is at or below 0.50; and for 92% it is at or below 0.75.

- Only 8% of the global population can expect to be 75% as productive as they could be.

- In the case of India, given its score of 0.44, a child born today will be only 44% as productive when she grows up as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health.

- The index shows learning adjusted years of school at an average of only 5.8 years and total expected years of school at 10.2 years.

- On the harmonised test scores matrix, students in India score 355 on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment.

- Probability of survival to age 5 is 96 out of 100.

- It finds 38 out of 100 children are stunted, and so are at risk of cognitive and physical limitations that can last a lifetime.

- The government has rejected the findings, saying it does not reflect the key initiatives that are being taken for developing human capital in the country, such as

○Samagra Shiksha, Ayushman Bharat Programme, Swachh Bharat Mission, Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Jandhan Yojana and the Aadhaar identification system-enabled direct cash transfer, that have improved governance and social protection.

- “These initiatives are transforming human capital in India at a rapid pace and very comprehensively touching upon the lives of millions of people living in rural and tribal areas.

- The Government of India, therefore, has decided to ignore the HCI.

Global Social Mobility Index

- India has been ranked very low at 76th place out of 82 countries on a new Social Mobility Index, while Denmark has topped the charts.

- Compiled by the World Economic Forum.

- Lists India among the five countries that stand to gain the most from a better social mobility score that seeks to measure parameters necessary for creating societies where every person has the same opportunity to fulfil his potential in life irrespective of socioeconomic background.

- Increasing social mobility, a key driver of income inequality, by 10% would benefit social cohesion and boost the world’s economies by nearly 5% by 2030.

- Measuring countries across five key dimensions distributed over 10 pillars —

○health;

○education (access, quality and equity);

○technology;

○work (opportunities, wages, conditions); and

○protections and

○institutions (social protection and inclusive institutions) —

■shows that fair wages, social protection and lifelong learning are the biggest drags on social mobility globally.

- In the case of India, it ranks 76th out of 82 economies. It ranks 41st in lifelong learning and 53rd in working conditions.

- The Areas of improvement for India include social protection (76th) and fair wage distribution (79th).

- The top five are all Scandinavian, while the five economies with the most to gain from boosting social mobility are China, the United States, India, Japan and Germany.

- The most socially mobile societies in the world, according to the report’s Global Social Mobility Index, are all European.

- The Nordic nations hold the top five spots, led by Denmark in the first place (scoring 85 points), followed by Norway, Finland and Sweden (all above 83 points) and Iceland (82 points).

- Rounding out the top 10 are the Netherlands (6th), Switzerland (7th), Austria (8th), Belgium (9th) and Luxembourg (10th).

- Among the G7 economies, Germany is the most socially mobile, ranking 11th with 78 points, followed by France in 12th position. Canada comes next (14th), followed by Japan (15th), the United Kingdom (21st), the United States (27th) and Italy (34th).

- Among the world’s large emerging economies, the Russian Federation is the most socially mobile of the BRICS grouping, ranking 39th, with a score of 64 points. Next is China (45th), followed by Brazil (60th), India (76th) and South Africa (77th).

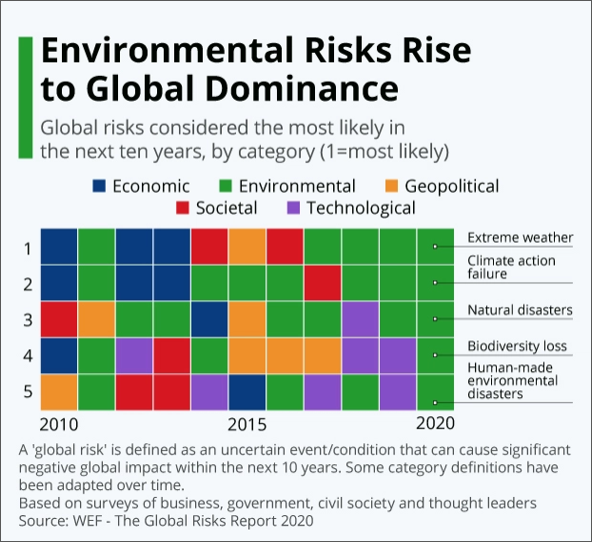

Global Risks Report 2020

- Released by The World Economic Forum.

- The first time in the report’s 10-year-history all of the top five issues that are likely to impact the world this year are environmental.

- The “top five global risks in terms of likelihood” are — extreme weather conditions, climate action failure, natural disasters, biodiversity loss and human-made natural disasters.

- In terms of potential impact, the top five risks are climate action failure, weapons of mass destruction, biodiversity loss, extreme weather, and water crises.

- In the previous decade, economic and financial crises were some of the most dangerous.

- The report states that global temperatures are set to rise by 3°C toward the end of this century.

- This is “twice what climate experts have warned is the limit to avoid the most severe economic, social and environmental consequences”.

Political instability

- The report foresees a year of increased domestic and international political instability and economic slowdown. Stating that geopolitical turbulence is propelling the world towards an unsettled era of great power rivalries, it asks leaders — both in businesses and governments — to work together in tackling “shared risks”.

Year of economic slowdown

- The report also forecasts a year of economic slowdown.

- The International Monetary Fund had expected growth to be at 3 per cent in 2019 — the lowest since the economic crisis of 2008-09.